Last week my daughter was covered in an alarming number of Band-Aids. She looked as if she had been attacked by a bear cub.

Thankfully, there were no actual cuts or scrapes under said bandages. There may have been a couple bug bites and a freckle, but nothing that required protection from the outside world. She just really felt the need for Band-Aids for a couple days.

As most parents know, Band-Aids have magical healing powers. Ditch those essential oils, moms. A brightly colored unicorn bandage contains more healing power than an entire bottle of tea tree oil.

In fact, Band-Aid brand, I propose an entire marketing campaign around the paranormal healing power of your product. Everyone already knows that’s why you make licensed versions; for their mystical powers, not for actual effectiveness. You aren’t fooling anyone.

But beware, parents, not all Band-Aids are created equal. A bandage’s level of healing power directly correlates to what appears on its exterior. And here’s the tricky part: the same Band-Aid has a varying degree of effectiveness depending on which child it is being placed on. For example, on my daughter, a Trolls bandage works much better than a Cars bandage. But for my niece or nephew, it may be the opposite. This miracle cure is highly dependent on the patients’ unique personality.

Band-Aids aren’t the only miraculous cure in a parents’ bag of tricks. I have witnessed firsthand the healing power of a fuzzy ice pack in the shape of a dog face, as well as the immediate therapeutic response a mother’s kiss can have on her child’s knee.

What do all these remedies have in common? They all produce a beneficial effect that can’t be attributed to the properties of the treatment itself, and must therefore be due to the patient’s belief in that treatment: the renowned placebo effect.

This theory can also be applied to marketing. The concept behind neuromarketing, which combines marketing, psychology and neuroscience, is to collect information on how the target market would respond to a product or marketing stimuli as the first step to advertising it. In marketing, the placebo effect falls under this discipline.

A lot of marketing is about trying to achieve a placebo effect in the minds of customers, or getting consumers to think they are benefitting from your product—whether that benefit is real or imagined. Similar to treating a child’s owie with a bandage, consumers purchase all sorts of things they are hopeful will do what they want.

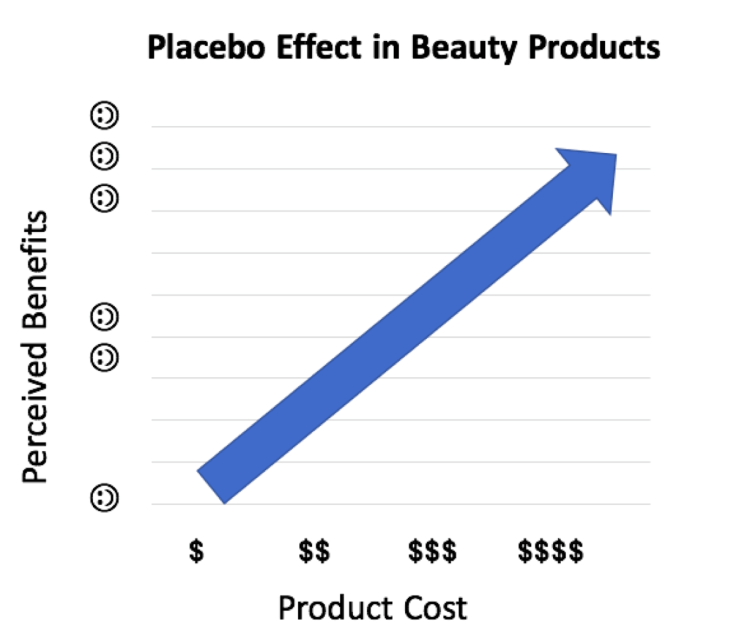

One of the best examples of the placebo effect in marketing is the beauty product industry. It will make my lashes appear longer? Yes, please! It will reduce my wrinkles by 33 percent? Take my $80, now. Do we really know if these products are doing what they claim? Nope. Do they make us feel better about our appearance? Oftentimes, yes. This seems disproportionately the case when we spend more money on them.

I realize this marketing strategy may seem a bit sketchy in theory, however, oftentimes it’s as innocent as putting a Band-Aid on a bug bite. Just look around at all the products you’ve purchased in which you have positive associations, yet can’t actually be sure they are doing what they claim.

We believe what we want to believe.

Love it. So she is a troll girl right now. I think Stella might associate most healing power with unicorns right now but troll may still be up there. Penny Dart Business Administrator St. Matthew 130 St. Matthews St Green Bay, WI 54301 920-435-6811

On Wed, Oct 10, 2018 at 9:09 PM Marketing Like a Mother wrote:

> April Marie posted: “Last week my daughter was covered in an alarming > number of Band-Aids. She looked as if she had been attacked by a bear cub. > Thankfully, there were no actual cuts or scrapes under said bandages. There > may have been a couple bug bites and a freckle, but no” >

LikeLike